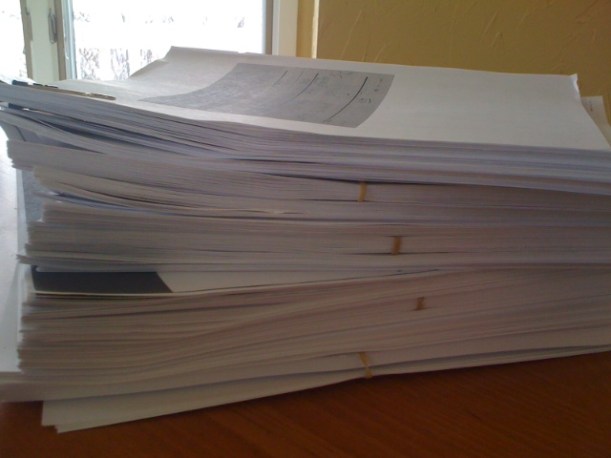

Yes, it has been about a year since I last posted. I have been up to my neck in research and have acquired roughly 800,000 words of notes thus far. I suppose it’s time to somehow put it all together in a cohesive (and coherent) form resembling a book.

I just returned from my second trip to Sacramento after spending 9 days at the State Archives poring over court transcripts, photographs, letters, and applications for pardon.

Thanks to the archives’ handy online database, I emailed them ahead of time with a list of documents I wanted to see. You’ll have to only imagine the happy-history nerd-researcher-writer dance I did when I saw the full cart of documents, ready for me to dive into. The wonderful archivists take their work very seriously and were happy to assist me with whatever I needed—they are a stellar group of people.

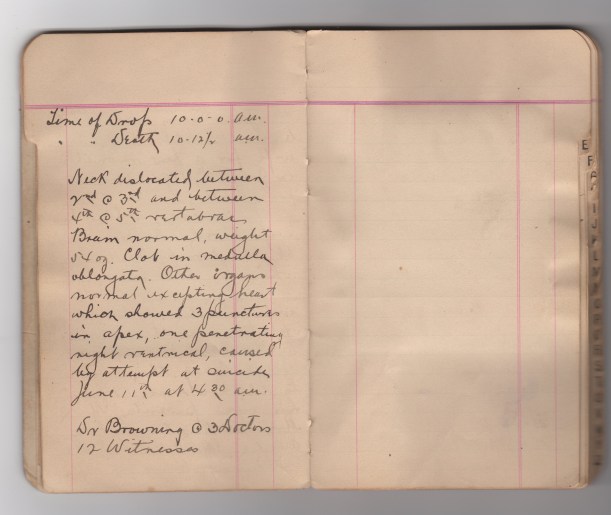

There is certainly a bit of anxiety that accompanies handling these old and delicate pages of history. In fact, many documents had never been looked at since being filed—the archivists actually had to cut open some of the envelopes containing materials, sealed decades earlier. A time capsule of sorts. I held hand-written letters from condemned men to the Governor, pleading for their lives.

With my laptop at the ready to take notes, I quickly realized my fingers couldn’t keep up with the amount of information to go through. I did the best I could, but in about 3 weeks, I should be receiving 620 copied pages from the archives. There was an overwhelming amount of history to dig through and I can’t tell you how fast 6-1/2 hours went by everyday in that research room.

At one point I opened up a box (Christmas—to a researcher) and found about 8 volumes of transcripts for just one inmate. But considering this particular condemned man racked up reprieved 9 times, there was bound to be a plethora of documents. This box represented a tiny fraction of the information on this man.

Staying in the downtown area, I walked everywhere. In fact, I compiled my own walking tour of crime scenes. I was surrounded by several different sites of where some crimes took place. At 17th and L stands the St. John’s Lutheran Church, once called the German Lutheran Church and where a ten-year-old girl became the victim of David Fountain, Folsom’s 31st hanging.

The pastor was kind enough to let me poke around the bell tower where the unfortunate young girl died of strangulation in 1914. It also happened to be one of the only areas of the church not renovated. I took several pictures, but as I got closer to the rickety old ladder leading to the belfry, I determined that was my limit.

At 12th and L, across the street from the State Capitol is the site of one of Sac’s most gruesome crimes. The Webers, an elderly couple were butchered in their home and place of business by Ivan Kovalev, a Russian who had escaped prison in Siberia. He became Folsom’s 2nd execution. The Hyatt Regency now occupies the site. All together, I walked past about 10 different sites, but most of the buildings or houses no longer exist.

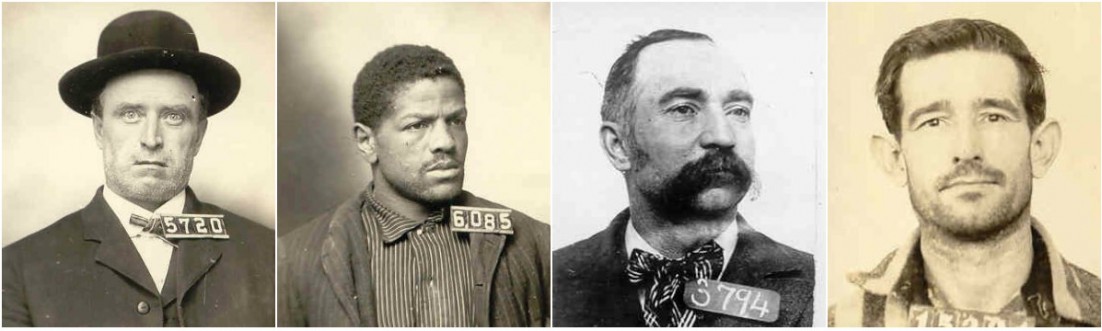

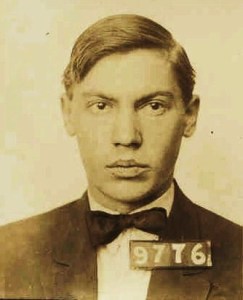

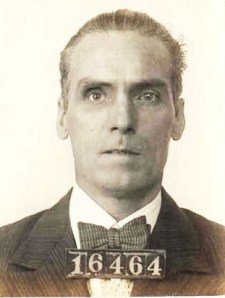

Ivan Kovalev

Ivan Kovalev

I even stumbled into Old Sacramento, a 28-acre National Historic Landmark District and State Historic Park along the Sacramento River. Aside from the loud motorcycles, cars, and swarms of tourists, you’d think you landed in the Wild West.

The old Supreme Court building still exists and is fully restored. However, because it is not handicapped accessible, it is closed to the public.

This area is also known as being the stage for many wars between two Chinese gangs in the mid 1800s to the early 1900s. This is where Lee Gong, a cigar shop owner was gunned down in his store, leading to Folsom’s very first execution: Chin Hane, an accused Highbinder, or Chinese hit man.

Across from the Capitol is the California Peace Officers Memorial, their names surrounding the memorial.

Ray Singleton, a guard at Folsom was killed as well as Warden Clarence Larkin, of Folsom and was the first and only warden of California’s penitentiaries to be killed while on duty.

Bra-less at Folsom Prison

My mom joined me for the last two days of the trip, so what’s the first thing I wanted to do? Go to Folsom Prison, of course. I contacted Lieutenant Paul Baker, Public Information Officer of the prison. After providing him with the proper information for background checks, he sent me some tour information, including a dress code. As you can imagine, hot pants and halter tops are frowned upon, so best to avoid those. Prison officials ask that you don’t wear denim, certain colors, certain fabrics, and absolutely no blue, orange, red or gold jumpsuits. For security purposes, avoid wearing metal such as jewelry and under wire bras. I spend a great deal of time telling my mother to make sure she brings an alternative and I’m the one who forgets. Assuming the process of a strip search would not be the highlight of my day, I was bra-less at Folsom prison. I wore a few layers. I was more disappointed I couldn’t bring in a camera. I document everything, so unable to take pictures while on this tour was agony. I’d like to give a very, very big thank you to Linda Tucker, of Linda’s Koality Photography who allowed me to use many of the following pictures. She supplies many of the current Folsom prison photographs on the Folsom Prison Museum’s website and was so incredibly nice to let me use the photos (even after I posted them). Thank you, Linda!

We arrived at the prison ready, but not having the slightest idea as to what the tour entails. We were told to wear good shoes and be prepared for 2-3 hours of walking. When the Entrance Gate Officer asked us if someone had explained The Hostage Policy to us, I could tell my mother contemplated backing out, but I was bound and determined to go through with it. Basically, The Hostage Policy is to ensure the convict does not escape, so if I’m in the way…well, that’s the risk I take. We were told that if you start to panic, just look up. Stationed throughout the prison, above and out of reach of inmates, are guards with guns. There’s always someone watching.

Don’t expect your tour guides to carry guns—officers at Folsom have never carried such weapons, as they can easily be used against them. Instead, they carry a baton, a whistle, and cans of defensive pepper spray.

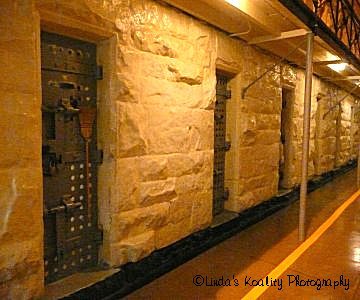

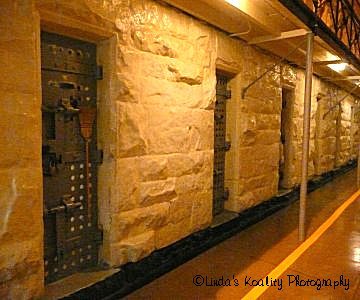

The prison is 130 years old and all of the original buildings are still in use, including the cell blocks—they are still opened and closed with a key, as the Entrance Officer explained, it’s just like Barney Fife in Mayberry. Well sort of. In fact, the prison didn’t install metal detectors until recently.

Dragging my mother along, we entered through the famous East Gate where we met Officer Hamblen, who would be accompanying us on the tour.

Being surrounded by the formidable gray granite walls (built using convict labor) is quite extraordinary. The walls are 30 feet tall and buried 15 feet deep. Digging your way out is impossible.

One of the “sites”on the tour were the conjugal visit rooms—an unscheduled stop—on this typical tour. Lucky us, huh? Just as we entered, we were informed that it hadn’t been cleaned, so don’t touch anything. No problem. Not exactly the most romantic setting. Linoleum floors, furniture you’d see in a yard marked “FREE,” a bedroom, bathroom, living room, and a kitchen. After about a minute, even Lt. Baker was ready to leave. It’s important to prison officials to help keep the inmates and their families together, especially since those allowed to have these visits will eventually rejoin society.

Providing prisoners with work skills is very important as well. Next time you see a California license plate—think of Folsom, because that’s where it came from.

Yes, they really do make license plates. Every single license plate in California is made by prisoners at Folsom. This was our first encounter with the inmates of Folsom. Anywhere from 75-100 inmates were in the very loud factory manning the machines and presses. It was a little jarring, to say the least. We really had no idea what to expect on the tour, so if you’re not comfortable with the unpredictability and inability to control the surroundings, I highly recommend the tour!

We also learned that the print shop at Folsom is responsible for all California DMV records and even books are translated in Braille. Inmates are given ample opportunities to learn skills such as metal work and welding so that when they are eventually released, they have better chances of landing a legitimate job.

Walking through the factory, I tried to just keep my eyes and ears on Lt. Baker and Officer Hamblen and not on the men who seemed just as surprised to us, as we were of them. Thinking that would be the closest we’d get to the inmates, we were in for a big surprise. We stood by this gate:

and watched hundred of prisoners walk past us and out into the yard.

and watched hundred of prisoners walk past us and out into the yard.

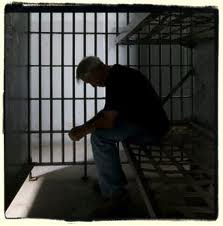

We entered into the main cell block, busy with activity. Inmates milled about, stood in groups, basically went about their daily business—oftentimes, just feet from us. Let me remind you, Folsom is filled with murderers, rapists, child molesters, drug dealers, gang members—you name it. (Lt. Baker informed us that there are four generations of gang members there.) One cell house had 5 tiers of cells—housing two to a cell. This is a 4×8 space for 2 people. It’s important we walked under the tiers and not down the center of building because you may get something thrown at you.

My mom had trouble in this area. Understandable. It wasn’t what we were expecting. She had a difficult time looking into the cells—as if she’d be invading their little space—a space that was really all they had to their name. She understood that they were in the clink for a reason, but it still bothered her. I on the other hand, had no qualms about that, especially as a history nerd and writer. Inmates are allowed to a have a 13” t.v and anything that can fit into 6 magazine/book boxes. I had the opportunity to go inside a single-occupancy cell to look around.

The occupant, who is a life-termer, was of course not in it at the time. The dimly-lit “room” was to be this man’s home for the rest of his life. The walls and shelves were covered with family photos and a few personal belongings that showed his life as a free man and the life of his loved ones since he’s been incarcerated. The vanity doors on his tiny sink were made of cardboard, as were some makeshift doors on a shelf above his bed. To think that this is where you’ll live out the rest of your life, is quite sad. However, at Folsom, 70% of parolees rescind and find themselves surrounded by gray granite again. To some, prison is a safer place than where they came from. Inside, you have the best health care, meds paid for, meals, routine, and a place to sleep. I imagine for some, that is more than what awaits them outside.

Still unaware of where we were headed, we passed a cell containing a man on suicide watch. The 60-something inmate freely told us that he tried to slash his throat. Following the officers, we walked past a dining room that feeds roughly 200 men at a time, overseen by two guards on the floor and one in a tower.

I was thrilled when I saw where we were headed next. Straight head, stenciled on a door, were the words, Condemned Row. This is where about 67 men were “ . . . hanged by the neck until dead.” (The death house was moved to another part of the prison in 1931.)

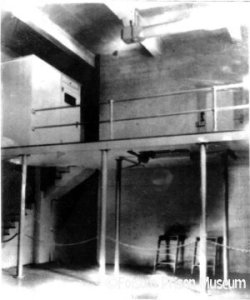

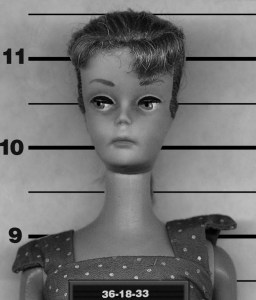

Death House, circa 1933

Death House, circa 1933

The original death house was long, narrow, and built of granite. The original 13 steps to the 2nd tier had been removed, but on the other end were a set of stairs leading to the very spot where the condemned men stood. I ran my hands along the gray stone. I also wasn’t going to miss the opportunity to stand inside one of the cells, so when it was offered, I wasted no time. It was surreal. The original steel doors had only a slot for a food tray to slide through. No light, no air. No fun.

There were cells on the lower and top half of the room and the men were rotated towards the top after each of their fellow inmates lost his life. Once a man was hanged, the others moved closer to the trap. When you reached the last cell on the top, and could hear your neighbor being hanged, you knew you were next. These men were constantly reminded of their fate—even from the time of trial. 12 jurors and a judge equals 13; 13 steps to the scaffold; 13 knots on a noose; 13 cells in condemned row. . .

I climbed the stairs to where these men were hanged. I reached the top and looked up to where a noose would have been hanging, then back down at the officers. The narrow room would have been packed full of spectators. At the top of the room and to the right of me were two small windows, each no bigger than 6”x6”. Lt. Baker said that the reasons for the windows varied. Some say it gave the man one last look of the sky before being executed. Others say they were put there to allow the hanged man’s spirit to leave. The room, once thought to teach murderers a lesson, is now being converted into a classroom.

We had to continue on, so we left the condemned row. At one point to our left, men were taking showers in an open room—concealed only by a half-wall. We just looked to our right.

We passed the place Johnny Cash sang the famous “Folsom Prison Blues,” and ended up outside facing the main yard. Inmates filed out from different places around the prison and into the yard. Surely, they wouldn’t take us through the crowds of prisoners. Of course, by now, we knew anything was possible. We went across one end of the yard to where prisoners were lined up to go through the metal detector. We stood against the wall as their belongings, that fit into a clear or mesh bag, were searched, before letting them proceed.

To our dismay, Officer Hamblen was called away. Then there were three. My mom scooted closer to me—as if I’d be able to do anything. Lt. Baker led us out of this doorway and back into the yard.

Our destination was the chapel situated on the opposite side of the yard. Are you kidding me?! Lt Baker cautioned us to not step into the basketball courts as he led us through a crowd of inmates. This is probably the one time I truly felt frightened. I followed Baker and my mom. I had no idea who or what was behind me. Inmates were literally an arms-length away as they watched us; some laughing and jeering. The chapel seemed to edge farther away from us, not closer. I forgot to look up. I should have looked up for a little peace of mind. We passed Blood Alley, an area off the yard that is known for fights and you guessed it, bloody ones.

After what seemed like ages, we arrived at the chapel.

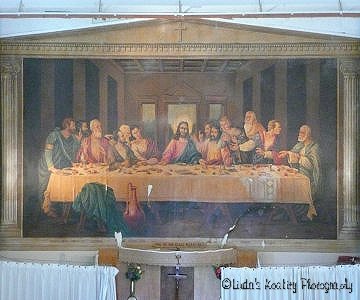

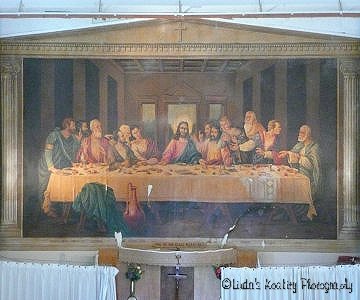

Inside, a few inmates prepared for a service. The highlight of the chapel is a 12’x21’ mural painted by convict, Ralph Pekor (often misspelled as “Pecor.”) in 1938, of DaVinci’s “Last Supper.” Before serving time for manslaughter, Pekor was an illustrator and set designer in Hollywood. The mural is stunning. A re-creation worthy of awe and admiration. If you didn’t know better, you’d think it was the original, that is, except for Pekor’s depiction of the different faces in the painting. They were said to be Pekor’s friends and fellow murderers or perhaps even prison staff. Pekor painted 12 other murals, but this is the only one remaining. Unfortunately, it is beginning to show its age prompting prison officials to try to come up with a way to safely preserve it.

We left the chapel and entered through a chain-link area where dozens of inmates were lined up, waiting to be let out into the yard. The Lieutenant was stopped by an inmate who had a concern. We stood there, waiting for this conversation to end, surrounded by prisoners. It was unnerving to say the least. However, throughout the tour, the inmates remained polite and we never heard them say anything to us.

Lt. Baker escorted us though another gate and away from anymore prisoners. The tour was coming to an end. The 2 ½ hours flew by, although my tour companion may disagree. We walked by the old Officers and Guards building that was the original entrance to the prison and is currently being renovated.

Nearby is Tower 13, once housing cells in the dungeon, now sporting only a ladder to the top where a guard is stationed. Some staff say it’s the one place on the property where they feel uncomfortable in, as if it’s inhabited with bygone prisoners.

As the tour concluded back at the Entrance Gate, we were exhausted; physically and mentally. Of course, the experience wasn’t over. Just outside the prison entrance is the Folsom Prison Museum, run by the Retired Correctional Peace Officers (RCPO).

The curator, Jim Brown, put in 32 years at the prison and is author of Folsom Prison, part of the Images of America series.

I also had the pleasure of meeting Dennis Sexton, who retired after 31 years of service at Folsom and Julie Davis, who was one of the first women guards at the prison. She spent 27 years and two pregnancies as a guard. Unbelievable.

The museum is a non-profit organization that donates much of their proceeds to the American Cancer Society, Fisher House and Make-A-Wish programs. We had the incredible opportunity to sit down with these wonderful individuals and “talk shop.” I do hope they each write their memoirs because they have stories to tell. It was an unexpected treat to sit down and talk with them; I could have stayed there all day.

Unfortunately, we had to hit the road, but not before making new friends. They have generously offered to help me with any research I may need. Please take the time to check out the museum’s website and learn about the brave and wonderful people who are truly dedicated to preserving Folsom’s rich and fascinating history, one artifact at a time. You can tell that they love what they do and aren’t in it for anything other than wanting to share Folsom’s history and help those in the process.

The journey eventually had to come to an end, but after being away from my son and husband for 2 weeks, I was ready to return home. I think I am finally seeing the light at the end of this over-2-year tunnel and I plan to have a first draft done by this summer. In the meantime, a book proposal is completed for review.

If you are ever in the area, I recommend taking a tour of this 130-year-old landmark and visit the museum. And remember ladies, no under wire bras.