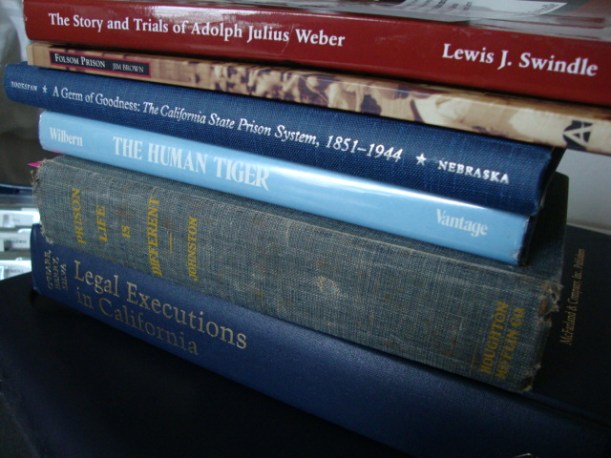

Many considered Folsom prison to be the “end of the line.” For some, that weighed heavily on their minds.

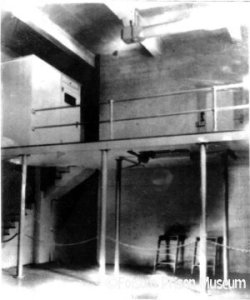

The formidable, gray granite walls and dark cramped cells did nothing for a prisoner’s morale. The prison was far from inviting, but would gladly swallow inmates up. Convicts spent much of their idle time formulating plots to escape: hiding in dark corners or under floorboards, taking prison officials hostage, or simply sneaking away from the yard. Folsom’s history is littered with tales of escapes, some successful, others not.

Prison authorities were well-aware of this and considered it when selecting a locale for the penitentiary. They chose the area based on several components: the rich granite deposits, the proximity of the American River, and the harsh surrounding terrain. Inmates saw these as inconveniences. On top of that, sentinel guards stood watch in towers holding gatling guns, trained to spot (and shoot) a fleeing inmate.

Folsom inmates were surrounded by reasons to not escape, yet it didn’t stop men from trying.

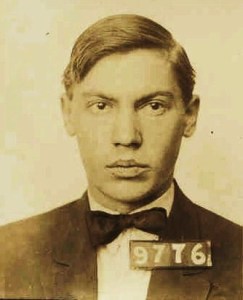

Carl F. Reese and a companion robbed a California theater in 1930, making off with nearly $4000. Captured in Waco, Texas, Reese returned to California to face trial. He failed to break from the county jail after cutting a hole through the brick of his cell using a sharpened file. Perhaps he knew escaping from Folsom prison wouldn’t be an easy task.

Nevertheless, he gave it the old college try.

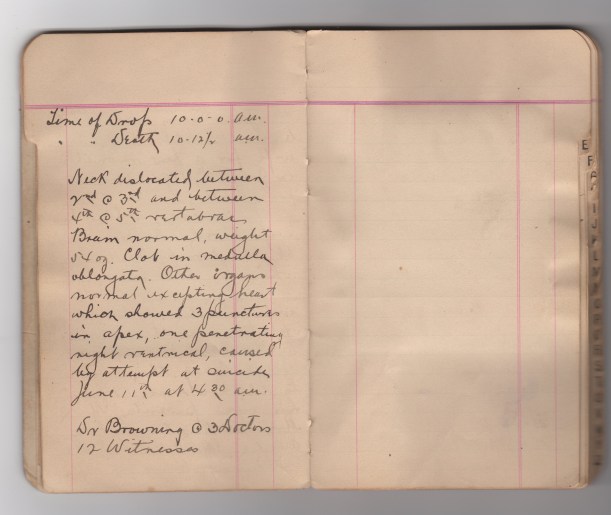

In September of 1932, guards reported Reese missing after he didn’t return from his work in the quarry. Searchers found a hole cut in the wire fence near the powerhouse, by the canal. Guards discovered Reese’s body on the bottom of the canal, his shoes weighed down with iron bars.

Using a rubber football bladder, Reese contrived a sort of diving helmet, complete with a glass eye piece. A rubber tube inserted into the helmet acted as a valve to provide air which was then attached to a tin can so it could float above water. Reese also fashioned an air pump out of a bicycle pump. He then used iron bars to weigh himself down, with the intention of walking along the bottom of the canal to freedom. Warden Court Smith surmised that the valve failed to work, therefore, allowing water to pour into the convict’s helmet. Unable to swim to the top due to the heavy weights in his shoes, Reese drowned.

Considering the amount of items used, it could be assumed that Reese’s escape plot began to take shape the moment he stepped into the prison, collecting the parts and tools to construct his makeshift scuba suit. Officials found a second helmet on the edge of the canal, apparently abandoned by a companion who witnessed the suit’s inventor drown. Probably a wise decision.