First of all, “insanity” is a legal term but in the medical profession, the preferred term is “intellectual disability.”

This is not to be confused with diminished capacity which is defined as an impaired mental condition, caused by disease, trauma, or intoxication but short of insanity, that can reduce the criminal responsibility of a defendant. Not all states allow defendants to offer this plea in response to criminal charges.

Albert Einstein defined insanity as, doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

Today, the American Law Institute Model defines it as: a defendant is not responsible for criminal conduct “if at the time of such conduct as a result of mental disease or defect he lacks substantial capacity either to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of the law.” The test thus takes into account both the cognitive and volitional capacity of insanity.

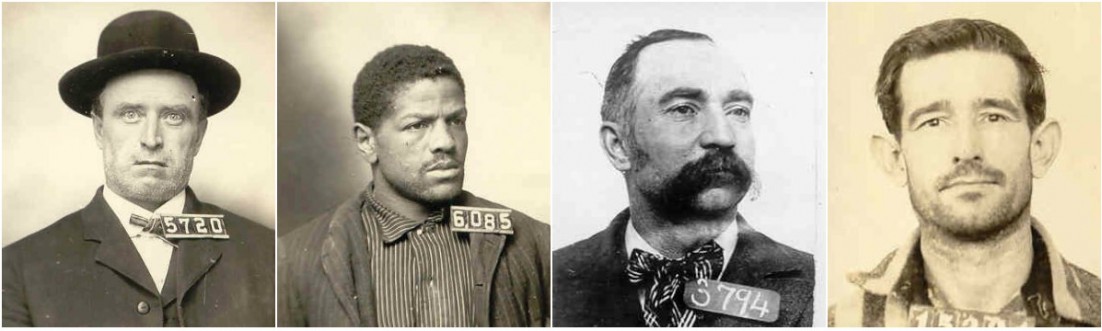

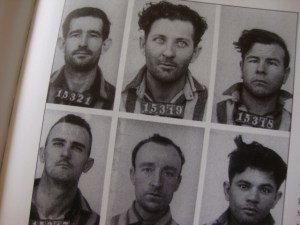

Eighteen of the ninety-three men executed at Folsom prison, had pleaded insanity at least once during their legal process.

#41, James Tyren murdered his 2 children

#41, James Tyren murdered his 2 children

#81, Mike Lami murdered his wife

#81, Mike Lami murdered his wife

In 1924, #45 Alex Kels underwent a procedure to have fluid extracted from his spine in an attempt to determine if a suspected case of syphilis had infected his brain, causing him to murder his victim. This test rocked the state of California and engaged governor Friend Richardson and the state prison board in a nasty debate that waged on for weeks.

Robert Wilbur of Truthout wrote a fascinating article entitled, “Killing the Mentally Ill.” I encourage you to read the article—I found it extremely eye opening. In 2002, the United States Supreme Court ruled that it was “cruel and unusual punishment,” to execute an inmate deemed “mentally retarded,” therefore, a violation of the 8th Amendment. And exactly how easy is it for the defense to prove their client is insane, or was during the commission of the crime? In the article, Wilbur talks with death penalty lawyer, George Kendall who often sees those with mental illness face the death penalty. “The prosecutors have the upper hand,” he said. It comes down to money. The state can shell out thousands of dollars to hire experts, where the defense has little money and is faced with the burden of proof. The paycheck these experts walk away with can be well over $200,000.

Wilbur noted one such expert, Michael Welner, MD who is proposing to create a “depravity scale” seeking to add an element of “evil” into the definition of some crimes. He strives to define the “worst of the worst” and help determine the truly evil crimes that deserve the death penalty. Uh . . . how exactly is evil defined? Can a panel of 12 peers determine that?

James L. Knoll IV, a senior forensic psychiatrist, vehemently rejects such a proposal. “Embracing the term ‘evil’ in the lexicon and practice of psychiatry will contribute to the stigmatization of mental illness, diminish the credibility of forensic psychiatry, and corrupt forensic treatment efforts.”

According to the Death Penalty Information Center, a man with an IQ of 69, confessed to a crime he didn’t commit, and after serving sixteen years behind bars, DNA evidence exonerated him.

It is estimated that of the 3200+ inmates on death row in the U.S., roughly 5-10% are considered to have intellectual disabilities. No surprise, but Texas has executed 24 mentally impaired people since 1977—the most out of any state.

In January of this year, Colorado governor, Bill Ritter issued a posthumous pardon to Joe Arridy. After reviewing evidence, Ritter found that Arridy, who had the mental capacity of a toddler, should not have lost his life for complicity to a 1936 murder.

WHAT DO YOU THINK? SHOULD THE MENTALLY ILL BE EXECUTED?