I’m often asked if I believe any of Folsom’s 93 were innocent. “Absolutely,” I usually reply, but can I prove it? Possibly, but when we’re talking about crimes from well over a hundred years ago, original evidence is long gone. Early investigation methods didn’t include the use of crime scene tape, latex gloves, or handy Ziploc bags to preserve and protect evidence. And DNA? Forgetaboutit! That technology came in the mid-1970s. Universal fingerprinting didn’t come along until the 1940s and before that, correctly identifying suspects by their prints oftentimes proved to be unreliable and inaccurate. At the turn of the 20th century, “beyond a reasonable doubt” didn’t exist and a few of the 93 hung by the threads of circumstantial evidence.

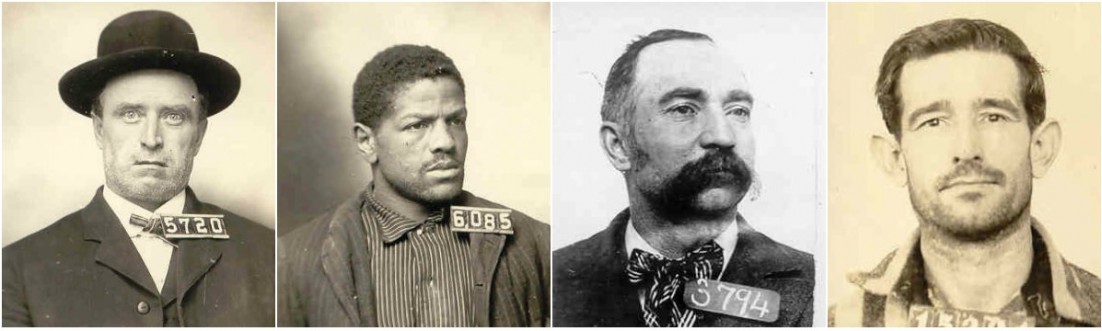

Little could separate the guilty from the innocent: a strand of hair resembling the victim found on or near the suspect, association with known criminals, or the color of your skin . . .

Not surprising, many of Folsom’s condemned minorities were doomed the moment of arrest; referred to in the newspapers as the N-word, half-breeds, or ignorant. Even their court-appointed attorney didn’t always have their client’s best interests at hand, or they themselves experienced backlash over representing a minority. The language barrier provided another opportunity for the law to take advantage of a foreign-born suspect, especially since interpreters were few and far between. Investigators easily manipulated an interrogation or testimony by using words the accused couldn’t comprehend.

Judges also didn’t sequester juries to the extent they do today, nor were the juries protected from “tampering.” After the selection of the 12 peers, newspapermen often printed the full names of the jurors in the next day’s issue. Jurors were even often caught dozing off, or snoring away during the trial. Did the judge reprimand the sleepy juror? No.

For some, the appeals process didn’t offer much hope either. Defense attorneys often bowed out after a jury found their court-appointed client guilty. The condemned man had only the hope that the governor would heed his plea for clemency or pardon.

Throughout the course of my research, I struggled to see how some of these men could be found guilty. I think it’s ignorant to assume they each received a fair trial and due process of the law. Today, technology has aided investigators when solving crimes and in many cases, free the wrongfully convicted.

The Innocence Project is a nonprofit organization dedicated to proving the innocence of those convicted of a crime they didn’t commit. Since its start in 1992, the organization has exonerated 268 people, including 17 who sat on death row. Despite the advances in crime investigation, it’s apparent these methods can’t always stop innocent people from going to prison and for some of Folsom’s 93, this potentially life-saving technology came too late.

May 2, 2011 at 11:51 am

Another fascinating post!

May 16, 2011 at 6:44 am

Great post! I always like your stuff. You have such cute titles too. Check out Level 2 Background Screening.

May 23, 2011 at 12:19 pm

Thanks, Alicia!